A preview of a featured article from the March, 2013 edition of Fire Safety Science News #34:

by Charles R. Jennings

John Jay College of Criminal Justice

The City University of New York, USA

The topic of fire during hurricanes has received scant attention in the scholarly fire engineering community and even in the trade press. While common sense clearly suggests that damage attendant to a hurricane and hazards of utilities and temporary measures for their restoration would produce heightened risk, particularly following an event, a casual review of scholarly indexes shows scarcely any mention of the topic. Hurricane Sandy will be remembered for its widespread swath of destruction. The images of fire-scarred Breezy Point, a community in New York was but one of several large fires that caused unprecedented damage in the City of New York on October 29-30, 2012.

While calls for emergency services were heightened throughout the City, the geography of the Rockaway Peninsula and its location on the southeastern border of the City made it the most severely exposed (along with Staten Island) to the storm’s effects. Remarkably, there were no deaths or significant injuries reported to responders or residents in these historic fires.

One point that is common to all these fires was flooding. The bulk of the Rockaways were inundated throughout

Looking north from the area of origin.

this event. However, because flooding was a result of both ocean tidal and storm surge effects, the water levels rose quickly and varied throughout the events. At their heights, water levels were sufficiently high as to prevent movement of even heavy vehicles – preventing the intervention of the local fire services – the Fire Department of New York (FDNY).

The other factor critical to these events was wind. With gusts reported up to 75 miles per hour (120 km/h) and sustained winds coming from the southeast, fire spread was driven by wind currents.

Breezy Point

Breezy Point is a beach enclave technically self-administering, located on the easternmost tip of the Rockaways. Originally established as a seasonal beach resort, it began with modest cottages and several resorts along the beach. Over time, it grew in to more substantial year-round occupation and many of the original cottages were improved or replaced with multi-story homes of conventional design. The physical plan of the fire area consisted of closely spaced dwellings separated by as little as a few feet (~1m) — with decks, porches and other features making a nearly- continuous field of combustibles. The street plan (refer to map) consisted of alternating narrow streets and smaller, paved paths designed to be navigated on foot or in compact service vehicles. Construction was almost exclusively timber framed, with older cottages typically built on pilings and more recent homes equipped with masonry or poured concrete foundations and basement stories.

First reported at 1830, the fire was first reported at 173 Ocean Avenue. The extraordinary conditions faced by responders during the storm were illustrated by FDNY Assistant Chief Joseph Pfeiffer’s recollections about reaching the blaze. He reported winding through darkened streets, turning back to avoid fallen trees, driving through water, and ultimately having to stop as he crossed the Marine Park Bridge, which links Brooklyn to the Rockaway Peninsula over Jamaica Bay. “There was three feet of water on the far end of the bridge. I had to park my fire department sedan, and ended up boarding an Engine Company to ride into the scene. Water was up to the headlights as we drove toward the glow.”

Companies operating relied on drafting standing water in a large parking are on the north side of the blaze, and made use of hydrants – some of which were used only after firefighters made connections by diving into the floodwaters and connecting hoses by feel amid the storm. Figure 2 (left) shows the view of the damage looking north from near the point of origin.

Driven by the strong winds coming directly off the ocean, the fire spread from house to house in the densely packed enclave. Chief Pfeiffer credited stopping the fire to being able to position resources ahead of the moving fire, and being ready to exploit an opportunity when winds shifted early in the morning of the 30th. He cautioned that had the winds not shifted, that the fire could well have continued to the west. The fire was declared under control at approximately 0630 on the 30th. The fire destroyed some 126 homes and damaged another 22. The effects of manual fire suppression efforts are apparent as the demarcation of destroyed and damaged homes is very clear (Figure 2 left).

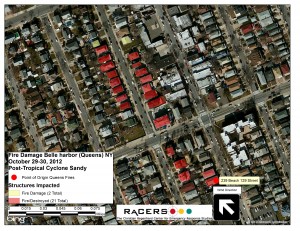

Belle Harbor

The Newport Avenue fire is perhaps the most interesting from the perspective of fire spread. Occurring in a predominantly residential neighborhood of detached 1-2 family dwellings, this fire was also driven by the wind, and exhibited a remarkable path of travel. Although timber frame buildings appeared to fare poorly, there were notable examples of fire extending into and through masonry structures as well.

Figure 2 (right) shows the pattern of damage for this fire. The fire began on Beach 129 Street in a 2-family timber frame house (Figure 3), extended to an adjacent brick exterior 2-family house, driven by winds it moved across backyards, possibly into a detached car storage structure and spread to three houses in a row on Beach 130th Street. The last of these houses was a masonry exterior home on the corner of Newport Ave and Beach 130 Street. The fire, driven by high winds, spread via a likely combination of flying brands, across the Newport Avenue (shown running left to right across the photo) and into a 2-story masonry-faced commercial building housing a restaurant. Despite its being detached, and surrounded on three sides by streets or a parking lot, the fire spread in two directions count – northward along Beach 130 Street, and across the west side of Beach 130 Street, where it consumed an additional 16 buildings[1]. Thirty-two buildings were destroyed in all. The fire was stopped mid-block with a brick-walled home suffering significant fire damage on the west side of the street, and a large timber frame home suffering damage to vinyl siding on its façade. The home on the east side of the street had a larger space between the fire and the other houses on the block. Fire suppression stopped this fire from spreading further, and like the others, firefighting was delayed because of high water levels.

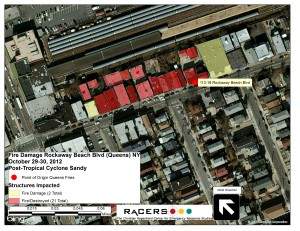

Rockaway Beach Blvd.

The Rockaway Beach Boulevard fire occurred in a commercial strip of buildings predominantly of ordinary construction (masonry exterior walls and timber interiors with some incidental steel structural members). The buildings ranged in height from 1 to 3 stories.

Interestingly, the fire spread was constrained by its location adjacent to a rail yard, which prevented its spread to the north. A masonry building with no windows abutting the building of origin prevented spread to the east, while a gap of roughly 3 feet (0.9 m) and fire service intervention limited spread on the western end of the block, although the building exposed suffered some damage, mainly scorching of its façade. This building was of brick and timber joist construction, which likely prevented the propagation of the fire and permitted successful intervention by fire services. Sixteen buildings were destroyed. Figure 4 shows damage resulting from this fire.

Summary

Three concurrent large fires in a relatively small geographic area of an island is highly unusual in New York City. The spread of fire between brick or stone facade buildings was worthy of further study, as was the transmission of fire across a wide thoroughfare in the Belle Harbor fire. The extraordinary efforts of the FDNY were instrumental in stopping these well-developed fires and point out the need for well-staffed and equipped fire services during extreme events not commonly thought to be “fire” emergencies.

References and Acknowledgments: Information on cause and origin and numbers of buildings damaged or destroyed came from FDNY Media Advisory “Fire Marshals Determine Causes of Several Major Fires from the Night of Super Storm Sandy – Including Breezy Point Fire Which Destroyed 126 Homes” December 24, 2012 online. Field investigation and photography was assisted by Chaim Roberts of the Christian Regenhard Center for Emergency Response Studies at John Jay College. Mapping was donated by Tom Vaughan of Manitou, Inc., Peekskill, NY. We acknowledge the assistance of several members of the FDNY who provided information to support this effort.

[1] The official number of buildings was determined by counting addresses destroyed – the count made after the fire by the author relied only on foundations and aerial imagery to establish a count.

Dr Natalia Flores-Quiroz is a researcher with experience in fire safety engineering. She worked for five years as a fire safety engineer in the mining industry before joining academia. She holds a MSc in fire safety from Ghent University, and her PhD focused on Fire investigations in Informal Settlements. Currently she is a lecturer at Stellenbosch University, where her main research areas are reconstruction of incidents in low-income settlements (i.e., informal settlements, refugee camps) and wildland urban interface (WUI) fires.

Dr Natalia Flores-Quiroz is a researcher with experience in fire safety engineering. She worked for five years as a fire safety engineer in the mining industry before joining academia. She holds a MSc in fire safety from Ghent University, and her PhD focused on Fire investigations in Informal Settlements. Currently she is a lecturer at Stellenbosch University, where her main research areas are reconstruction of incidents in low-income settlements (i.e., informal settlements, refugee camps) and wildland urban interface (WUI) fires. Bronwyn Forrest is a 3rd year PhD student at the University of Waterloo, conducting multi-disciplinary research investigating human physiological response to fire exposure. Bronwyn graduated in 2017 with a BSc. Honours Kinesiology and in 2020 with a MASc. Mechanical & Mechatronics Engineering (Heat Release Rate in Ventilation-Limited Furniture Fires) before merging her two degrees in her PhD research. As a senior graduate student in the Fire Research Group, Bronwyn spear-heads large-scale fire experiments, mentors junior graduate and undergraduate students, and has recently set-up a new ‘human exposure lab’ at the Fire Research Facility where she leads new research in that area. Since her induction into the world of fire science, Bronwyn has grown more and more passionate about the multi-faceted nature of emerging fire safety challenges. Through innovative research, she hopes to make meaningful contributions that help shape changes to fire safety over the course of her career.

Bronwyn Forrest is a 3rd year PhD student at the University of Waterloo, conducting multi-disciplinary research investigating human physiological response to fire exposure. Bronwyn graduated in 2017 with a BSc. Honours Kinesiology and in 2020 with a MASc. Mechanical & Mechatronics Engineering (Heat Release Rate in Ventilation-Limited Furniture Fires) before merging her two degrees in her PhD research. As a senior graduate student in the Fire Research Group, Bronwyn spear-heads large-scale fire experiments, mentors junior graduate and undergraduate students, and has recently set-up a new ‘human exposure lab’ at the Fire Research Facility where she leads new research in that area. Since her induction into the world of fire science, Bronwyn has grown more and more passionate about the multi-faceted nature of emerging fire safety challenges. Through innovative research, she hopes to make meaningful contributions that help shape changes to fire safety over the course of her career. Dr. (HDR) Eric Guillaume has worked in fire sciences since 1998. He formerly led the fire behaviour department of SNCF (French Railway), then changed company in 2005 to join LNE (The French National Laboratory for Testing and Metrology) as head of Fire safety studies department, and later as head of research for whole testing activities of LNE. Nowadays (since 2015), he works for Efectis France, first as Technical Director and more recently as General Manager of the company, leading one of the most important fire testing and fire safety engineering companies in Europe (With approx. 180 people and 28 M€ turnover)

Dr. (HDR) Eric Guillaume has worked in fire sciences since 1998. He formerly led the fire behaviour department of SNCF (French Railway), then changed company in 2005 to join LNE (The French National Laboratory for Testing and Metrology) as head of Fire safety studies department, and later as head of research for whole testing activities of LNE. Nowadays (since 2015), he works for Efectis France, first as Technical Director and more recently as General Manager of the company, leading one of the most important fire testing and fire safety engineering companies in Europe (With approx. 180 people and 28 M€ turnover) Dr. Albert Simeoni is Professor and the Department Head of Fire Protection Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). He is the WPI site director of the Wildfire Interdisciplinary Research Center (WIRC), an Industry-University Cooperative Research Center (IUCRC) of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the United States. Dr. Simeoni has served IAFSS by being chair or co-chair of the Wildland Fire track (2014, 2020 and 2023), Co-chair of the Awards Committee for the Best Thesis Awards (2023), Associate-Editor of Fire Safety Journal (2010-2015), member of the Editorial Board of Fire Safety Journal (since 2016), and Contributing Editor of Fire Safety Science News (since 2011).

Dr. Albert Simeoni is Professor and the Department Head of Fire Protection Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). He is the WPI site director of the Wildfire Interdisciplinary Research Center (WIRC), an Industry-University Cooperative Research Center (IUCRC) of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the United States. Dr. Simeoni has served IAFSS by being chair or co-chair of the Wildland Fire track (2014, 2020 and 2023), Co-chair of the Awards Committee for the Best Thesis Awards (2023), Associate-Editor of Fire Safety Journal (2010-2015), member of the Editorial Board of Fire Safety Journal (since 2016), and Contributing Editor of Fire Safety Science News (since 2011). Brian J. Meacham, PhD, PE (CT&MA), EUR ING, CEng (UK), FIFireE, FSFPE, is the Managing Principal of Meacham Associates. He develops risk-informed performance-based solutions to complex building and infrastructure challenges, provides peer-review services, and undertakes building and fire regulatory system studies. He also conducts research in these areas as well as in sustainable and fire resilient built environments and fire safety technologies. Brian has authored more than 300 publications, given more than 300 presentations and has been awarded more than $4M in research funding. His prior positions include Associate Professor of Fire Protection Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Principal at Arup, Technical Director and Research Director at SFPE, and fire safety engineer in Europe and the USA. Brian is Chair of the ICC Performance Code Committee, Chair of the NFPA Technical Committee on Fire Risk Assessment Methods, Immediate Past Chair of the International Association for Fire Safety Science (IAFSS), a Past President of the SFPE, and a past Chair of the Inter-jurisdictional Regulatory Collaboration Committee (IRCC). He is a licensed Professional Engineer in CT and MA, a Chartered Engineer and Fellow of the Institution of Fire Engineers (UK), a registered European Engineer (EUR ING), a Fellow of the SFPE, and a Fulbright Global Scholar.

Brian J. Meacham, PhD, PE (CT&MA), EUR ING, CEng (UK), FIFireE, FSFPE, is the Managing Principal of Meacham Associates. He develops risk-informed performance-based solutions to complex building and infrastructure challenges, provides peer-review services, and undertakes building and fire regulatory system studies. He also conducts research in these areas as well as in sustainable and fire resilient built environments and fire safety technologies. Brian has authored more than 300 publications, given more than 300 presentations and has been awarded more than $4M in research funding. His prior positions include Associate Professor of Fire Protection Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Principal at Arup, Technical Director and Research Director at SFPE, and fire safety engineer in Europe and the USA. Brian is Chair of the ICC Performance Code Committee, Chair of the NFPA Technical Committee on Fire Risk Assessment Methods, Immediate Past Chair of the International Association for Fire Safety Science (IAFSS), a Past President of the SFPE, and a past Chair of the Inter-jurisdictional Regulatory Collaboration Committee (IRCC). He is a licensed Professional Engineer in CT and MA, a Chartered Engineer and Fellow of the Institution of Fire Engineers (UK), a registered European Engineer (EUR ING), a Fellow of the SFPE, and a Fulbright Global Scholar. Kazunori Harada is a professor of architecture & architectural engineering at Kyoto University, Japan. He has a career in fire research for over 35 years. He has authored 14 IAFSS symposium papers. His expertise covers the fire resistance of construction materials, smoke movement and control, burning of combustibles in open and compartment, performance-based code & design of buildings and so on. He serves as a vice president of AOAFST, Asia-Oceania Association of Fire Science and Technology. He also serves as the Convenor of ISO/TC92/SC4 WG9, calculation methods for fire safety engineering (FSE), which develops calculation standards concerning FSE.

Kazunori Harada is a professor of architecture & architectural engineering at Kyoto University, Japan. He has a career in fire research for over 35 years. He has authored 14 IAFSS symposium papers. His expertise covers the fire resistance of construction materials, smoke movement and control, burning of combustibles in open and compartment, performance-based code & design of buildings and so on. He serves as a vice president of AOAFST, Asia-Oceania Association of Fire Science and Technology. He also serves as the Convenor of ISO/TC92/SC4 WG9, calculation methods for fire safety engineering (FSE), which develops calculation standards concerning FSE. Dr Xinyan Huang is an Associate Professor at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Deputy Director of the Research Centre for Fire Safety Engineering. He received his PhD from Imperial College London, MSc from UC San Diego, and BEng from Southeast University, and was a Postdoc at UC Berkeley. Dr Huang is a Combustion Scientist and a Fire Safety Engineer who has co-authored over 200 journal papers. He is an Associate Editor of Fire Technology and International Journal of Wildland Fire, an editorial member of J. Building Engineering, Fire Safety J. and Fire and Materials, a Chartered Building Services and Fire Engineer, a committee member for HK Fire Safety Code, and a Fire Expert for HK High Court. He receives the NSFC Excellent Young Scientists Fund, Bernard Lewis Fellowship and Sugden Best Paper Award from Combustion Institute, “5 under 35” and Bono Award from the Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE).

Dr Xinyan Huang is an Associate Professor at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Deputy Director of the Research Centre for Fire Safety Engineering. He received his PhD from Imperial College London, MSc from UC San Diego, and BEng from Southeast University, and was a Postdoc at UC Berkeley. Dr Huang is a Combustion Scientist and a Fire Safety Engineer who has co-authored over 200 journal papers. He is an Associate Editor of Fire Technology and International Journal of Wildland Fire, an editorial member of J. Building Engineering, Fire Safety J. and Fire and Materials, a Chartered Building Services and Fire Engineer, a committee member for HK Fire Safety Code, and a Fire Expert for HK High Court. He receives the NSFC Excellent Young Scientists Fund, Bernard Lewis Fellowship and Sugden Best Paper Award from Combustion Institute, “5 under 35” and Bono Award from the Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE).

Arnaud Trouvé is Professor and Chair in the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at the University of Maryland in College Park, USA. He joined the Faculty in 2001 with a Ph.D. (1989) and Engineering Degree (1985) from École Centrale of Paris, France, and with previous experience as a combustion research engineer. Professor Trouvé’s research interests include fire modeling and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD); application of data assimilation to fire and combustion; and physical modeling of combustion- and fire-related phenomena, including compartment fires, wildland fires and explosions. Professor Trouvé is a Fellow of the Combustion Institute and the recipient of the 2017 FORUM Sjölin Award. He has served on the editorial boards of the Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, Combustion and Flame, and Fire Technology, and is currently on the editorial boards of Combustion Theory and Modelling and the Fire Safety Journal. Professor Trouvé is also a past Chair of the US Eastern States Section of the Combustion Institute (ESSCI) and a past Member of the Executive Board of the International Association for Fire Safety Science (IAFSS). He is a co-Chair of a recent initiative endorsed by IAFSS and called the “IAFSS Working Group on Measurement and Computation of Fire Phenomena” (the MaCFP Working Group) and the past Chair of a new network of leading higher-education institutions and research laboratories in fire safety engineering called the International Fire Safety Consortium (IFSC).

Arnaud Trouvé is Professor and Chair in the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at the University of Maryland in College Park, USA. He joined the Faculty in 2001 with a Ph.D. (1989) and Engineering Degree (1985) from École Centrale of Paris, France, and with previous experience as a combustion research engineer. Professor Trouvé’s research interests include fire modeling and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD); application of data assimilation to fire and combustion; and physical modeling of combustion- and fire-related phenomena, including compartment fires, wildland fires and explosions. Professor Trouvé is a Fellow of the Combustion Institute and the recipient of the 2017 FORUM Sjölin Award. He has served on the editorial boards of the Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, Combustion and Flame, and Fire Technology, and is currently on the editorial boards of Combustion Theory and Modelling and the Fire Safety Journal. Professor Trouvé is also a past Chair of the US Eastern States Section of the Combustion Institute (ESSCI) and a past Member of the Executive Board of the International Association for Fire Safety Science (IAFSS). He is a co-Chair of a recent initiative endorsed by IAFSS and called the “IAFSS Working Group on Measurement and Computation of Fire Phenomena” (the MaCFP Working Group) and the past Chair of a new network of leading higher-education institutions and research laboratories in fire safety engineering called the International Fire Safety Consortium (IFSC). Dr Felix Wiesner is an Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia and study the role of engineered timber in fire safety. I work in the Faculty of Forestry as part of the Wood Science department. My research focus has mostly been experimental, considering fire dynamics in timber compartments and the structural fire capacity of engineered timber products. In addition, I am interested in the performance of timber in exterior building or infrastructure setting. This closely interfaces with wildfire considerations for the wildland urban interface (WUI), especially when it comes to smouldering.

Dr Felix Wiesner is an Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia and study the role of engineered timber in fire safety. I work in the Faculty of Forestry as part of the Wood Science department. My research focus has mostly been experimental, considering fire dynamics in timber compartments and the structural fire capacity of engineered timber products. In addition, I am interested in the performance of timber in exterior building or infrastructure setting. This closely interfaces with wildfire considerations for the wildland urban interface (WUI), especially when it comes to smouldering. Prof. Yuji Nakamura is Full Professor in Department of Mechanical Engineering, Toyohashi University of Technology (TUT), appointed as Affiliate Full Professor in Center for Fire Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science (since 2014). He currently serves the Head of Energy Conversion Laboratory and appointed as Department Chair since 2024. Prof. Nakamura has made professional service in Fire Science Community served as Management Committee of IAFSS during 2021-2023, worked as Co-chair of LOC in the most recent IAFSS symposium at Tsukuba, acting Associate Editor of Fire Technology since 2014 and board member of Fire Safety Journal since 2017.

Prof. Yuji Nakamura is Full Professor in Department of Mechanical Engineering, Toyohashi University of Technology (TUT), appointed as Affiliate Full Professor in Center for Fire Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science (since 2014). He currently serves the Head of Energy Conversion Laboratory and appointed as Department Chair since 2024. Prof. Nakamura has made professional service in Fire Science Community served as Management Committee of IAFSS during 2021-2023, worked as Co-chair of LOC in the most recent IAFSS symposium at Tsukuba, acting Associate Editor of Fire Technology since 2014 and board member of Fire Safety Journal since 2017. ROGAUME Thomas is an Professor at the University of Poitiers – Pprime Institute (UPR3346 CNRS), FRANCE.

ROGAUME Thomas is an Professor at the University of Poitiers – Pprime Institute (UPR3346 CNRS), FRANCE. Yu Wang is a professor at the State Key Laboratory of Fire Science, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC). He got joint Ph.D. from USTC and the City University of Hong Kong in 2016 and had working experience at the University of Edinburgh, Worcester Polytechnic Institute and National University of Singapore before returning to China in 2020. His primary research areas are high-rise building fire and large outdoor fire. Yu has published over 50 SCI journal papers, and is currently an Associate Editor in Fire Technology and Editorial Board Member in Fire Safety Journal. He initiated the first English fire course at USTC, Introduction of Fire Dynamics, reported by China News and People’s Daily Online (over 260,000 audiences). In recent years, he has received SFPE Global 5 Under 35 Award, Youth May Fourth Medal (Anhui Province), Young Faculty Career Award (USTCAF), and some Best Paper/Presentation/Poster/Image Awards in IAFSS or AOSFST.

Yu Wang is a professor at the State Key Laboratory of Fire Science, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC). He got joint Ph.D. from USTC and the City University of Hong Kong in 2016 and had working experience at the University of Edinburgh, Worcester Polytechnic Institute and National University of Singapore before returning to China in 2020. His primary research areas are high-rise building fire and large outdoor fire. Yu has published over 50 SCI journal papers, and is currently an Associate Editor in Fire Technology and Editorial Board Member in Fire Safety Journal. He initiated the first English fire course at USTC, Introduction of Fire Dynamics, reported by China News and People’s Daily Online (over 260,000 audiences). In recent years, he has received SFPE Global 5 Under 35 Award, Youth May Fourth Medal (Anhui Province), Young Faculty Career Award (USTCAF), and some Best Paper/Presentation/Poster/Image Awards in IAFSS or AOSFST. Brian Lattimer, Ph.D. is a Professor in Mechanical Engineering at Virginia Tech where he performs experimental and computational research on fire safety and disaster resilience. He has nearly 30 years of experience in fire related research. His research areas include material behavior in fires, fire dynamics, suppression agents, heat transfer from fires to surfaces, structural response during fire, and firefighting technology.

Brian Lattimer, Ph.D. is a Professor in Mechanical Engineering at Virginia Tech where he performs experimental and computational research on fire safety and disaster resilience. He has nearly 30 years of experience in fire related research. His research areas include material behavior in fires, fire dynamics, suppression agents, heat transfer from fires to surfaces, structural response during fire, and firefighting technology. Dr. Shuna Ni is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. She received her Ph.D. degree at Texas A&M University in 2018 and her Master’s degree at Tongji University in 2013. Dr. Ni’s research focuses on fire forensics, structural fire engineering, WUI fire resilience, fire safety of tall mass-timber buildings and fire-related multiple hazards. Her research has been funded by National Science Foundation, National Institute of Justice, Fire Protection Research Foundation, University Transportation Centers under the Department of Transportation, Grand Challenges Grants Program at the University of Maryland and industrial partners.

Dr. Shuna Ni is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. She received her Ph.D. degree at Texas A&M University in 2018 and her Master’s degree at Tongji University in 2013. Dr. Ni’s research focuses on fire forensics, structural fire engineering, WUI fire resilience, fire safety of tall mass-timber buildings and fire-related multiple hazards. Her research has been funded by National Science Foundation, National Institute of Justice, Fire Protection Research Foundation, University Transportation Centers under the Department of Transportation, Grand Challenges Grants Program at the University of Maryland and industrial partners. Dr Wojciech Węgrzyński is with ITB, that is the Polish Building Research Institute in Warsaw. He currently holds the position of the Deputy Head of Fire Research Department and the Professor of the Institute, and a Director at SFPE Europe. He is the Author of 40 peer-reviewed papers published in all of the primary FSE journals. His main area of interest is the fundamentals of compartment fire dynamics and standardized fire testing, and also: use of computational fluid dynamics in fire, wind and fire interaction and evaluation of the effects of the spread of smoke in buildings. His research is focused on the impact of the architectural context of the building on the smoke control performance, as well as finding solutions to make the smoke exhaust systems cheaper and more efficient. Member of the Sub-committee for Research of the IAFSS. 2018 NFPA Harry C. Bigglestone Award Recipient; 2019 Jack Watts Award Recipient; 2020 SFPE 5 Under 35 Award Recipient. Member of Editorial Board of ‘Fire Technology. Hosts a fire podcast at

Dr Wojciech Węgrzyński is with ITB, that is the Polish Building Research Institute in Warsaw. He currently holds the position of the Deputy Head of Fire Research Department and the Professor of the Institute, and a Director at SFPE Europe. He is the Author of 40 peer-reviewed papers published in all of the primary FSE journals. His main area of interest is the fundamentals of compartment fire dynamics and standardized fire testing, and also: use of computational fluid dynamics in fire, wind and fire interaction and evaluation of the effects of the spread of smoke in buildings. His research is focused on the impact of the architectural context of the building on the smoke control performance, as well as finding solutions to make the smoke exhaust systems cheaper and more efficient. Member of the Sub-committee for Research of the IAFSS. 2018 NFPA Harry C. Bigglestone Award Recipient; 2019 Jack Watts Award Recipient; 2020 SFPE 5 Under 35 Award Recipient. Member of Editorial Board of ‘Fire Technology. Hosts a fire podcast at  Jennifer Wen is currently Professor of Energy Resilience in the School of Mechanical Engineering Sciences, University of Surrey as Professor. Previously, Jennifer held positions at Computational Dynamics Limited (founding vendor of STAR-CCM), British Gas plc, South Bank University, Kingston University London, and University of Warwick. She is a Fellow of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and Vice-Chair for Research for the International Association for Fire Safety Science. Jennifer is also a member and sub-task leader of the European Safety Panel on Hydrogen Safety (EHSP) established by the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking (now Clean Hydrogen Partnership) of the European Commission. She is an Associate Editor for the Proceedings of the Combustion Institute.

Jennifer Wen is currently Professor of Energy Resilience in the School of Mechanical Engineering Sciences, University of Surrey as Professor. Previously, Jennifer held positions at Computational Dynamics Limited (founding vendor of STAR-CCM), British Gas plc, South Bank University, Kingston University London, and University of Warwick. She is a Fellow of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and Vice-Chair for Research for the International Association for Fire Safety Science. Jennifer is also a member and sub-task leader of the European Safety Panel on Hydrogen Safety (EHSP) established by the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking (now Clean Hydrogen Partnership) of the European Commission. She is an Associate Editor for the Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. Enrico Ronchi is an Associate Professor at Lund University, Sweden. His research and education activities are focused on evacuation and human behaviour in case of building fires and wildfires. His work has been published in over 150 publications (including >90 peer-reviewed journal papers). He is currently Associate Editor for the journals Fire Technology and Safety Science and member of the editorial board of the Fire Safety Journal.

Enrico Ronchi is an Associate Professor at Lund University, Sweden. His research and education activities are focused on evacuation and human behaviour in case of building fires and wildfires. His work has been published in over 150 publications (including >90 peer-reviewed journal papers). He is currently Associate Editor for the journals Fire Technology and Safety Science and member of the editorial board of the Fire Safety Journal.